About me

I am an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Syracuse University. Before joining Syracuse, I had postdoctoral fellowships at Umeå University and UNAM. I graduated from NYU in 2018, where I was one of the organizers of the New York Philosophy of Language Workshop. I am also the editor of PhilPapers' category on speech reports and one of the organizers of the Central New York Philosophy of Language Workshop. I specialize in philosophy of language, and I am interested in the points where it intersects with semantics and philosophy of mind.

I am an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Syracuse University. Before joining Syracuse, I had postdoctoral fellowships at Umeå University and UNAM. I graduated from NYU in 2018, where I was one of the organizers of the New York Philosophy of Language Workshop. I am also the editor of PhilPapers' category on speech reports and one of the organizers of the Central New York Philosophy of Language Workshop. I specialize in philosophy of language, and I am interested in the points where it intersects with semantics and philosophy of mind.

My main research focuses on foundational questions about non-ideal communication. In a series of papers, I develop a theory of non-ideal communication capable of explaining communicative success, disagreement, and attitude ascriptions even in cases of indeterminacy. If you are intrigued, email me at: mabreuza@syr.edu

My full last name is "Abreu Zavaleta". Kindly cite my work accordingly— i.e. as "Abreu Zavaleta, Martín"

Research

Completed

By year of acceptance, most recent first.

- Negotiated contextualism and disagreement data. 2023. Linguistics & Philosophy. (Abstract)

Suppose I assert "Jim is rich". According to negotiated contextualism, my assertion should be understood as a proposal to adopt a standard of wealth such that Jim counts as "rich" by that standard. Furthermore, according to negotiated contextualism, this is so in virtue of the semantic properties of the word "rich". Defenders of negotiated contextualism (Khoo 2020, Khoo and Knobe 2016) claim that this view is uniquely well-placed to account for certain disagreement data; for example, that if your standard for the application of the word "rich" is more constraining than mine, you can sensibly assert "no, Jim is not rich" without thereby making an incompatible claim. This paper outlines a simpler explanation of the data: speakers can sensibly reject a given assertion provided that they think that the asserted sentence is false in the context which they take to be relevant to that sentence's interpretation. I argue that, combined with standard semantic tools, this explanation can account for the original data and for new empirical results. Along the way, I present new empirical data to argue against negotiated contextualism. - Partial Understanding. 2023. Synthese (Abstract, Pre-print)

Say that an audience understands a given utterance perfectly only if she correctly identifies which proposition (or propositions) that utterance expresses. In ideal circumstances, the participants in a conversation will understand each other's utterances perfectly; however, even if they do not, they may still understand each other's utterances at least in part. Although it is plausible to think that the phenomenon of partial understanding is very common, there is currently no philosophical account of it. This paper offers such an account. Along the way, I argue against two seemingly plausible accounts which use Stalnaker's notion of common ground and Lewisian subject matters, respectively. - Inferences from utterance to belief. 2022. The Philosophical Quarterly. (Abstract, open access)

If Amelia utters 'Brad ate a salad in 2005' assertorically, and she is speaking literally and sincerely, I can infer that Amelia believes that Brad ate a salad in 2005. This paper discusses what makes this kind of inference truth-preserving. According to the baseline picture, my inference is truth-preserving because, if Amelia is a competent speaker, she believes that the sentence she uttered means that Brad ate a salad in 2005; thus, if Amelia believes that that sentence is true, she must believe that Brad ate a salad in 2005. I argue that this view is not correct; on pain of irrationality, normal speakers can't have specific beliefs about the meaning of the sentences they utter. I propose a new account, relying on the view that epistemically responsible speakers utter sentences assertorically only if they believe all the propositions which they think those sentences might mean. - Disagreement Lost. 2020. Synthese (Abstract, open access)

This paper develops a puzzle about not-merely-verbal disputes. At first sight, it would seem that a dispute over the truth of an utterance is not merely verbal only if there is a proposition that the parties to the dispute take the utterance under dispute to express, which one of the parties accepts and the ohter rejects. Yet, as I argue, it is extremely rare for ordinary disputes over an utterance’s truth to satisfy this condition, in which case non-merely verbal disputes are extremely rare. The consequences of the puzzle are twofold: on the one hand, it suggests we should reject seemingly natural accounts of what it is for a dispute not to be merely verbal; on the other, it suggests that the kind of problems of lost disagreement typically raised against contextualism arise for nearly everyone. After examining various responses to the puzzle, I outline a solution using the framework of truthmaker semantics. - Gómez-Torrente on reference to ordinary substances. 2020 Manuscrito, book symposium on Roads to Reference (Abstract, open access)

This note discusses Gómez-Torrente's solution to the arbitrariness problem for the Kripke-Putnam account of natural kind terms. - Communication and indifference. 2019. Mind & Language (Abstract, Pre-print)

According to the propositional view of communication, every literal assertoric utterance of an indicative sentence expresses a proposition; communication by means of such an utterance is successful only if the audience entertains the proposition(s) the speaker expressed. This view entails that, for every assertoric utterance of an indicative sentence, there is a proposition the audience must entertain in order for communication to be successful. According to a recent objection by Ray Buchanan, because the linguistic meaning of certain sentences involving quantifiers and definite descriptions underdetermines which proposition the utterance expresses, oftentimes there is no particular proposition the audience must entertain in order for communication to be successful. Using resources from situation semantics and MacFarlane's nonindexical contextualism, this paper develops a view of literal communication in the vicinity of the propositional view, but which is not susceptible to Buchanan's underdeterminacy considerations. Furthermore, as I argue, the proposed view accounts for the kind of indifference which, according to Buchanan, typically characterizes speakers' intentions. - Communication and Variance. 2019. Topoi (Abstract, Pre-print)

According to standard assumptions in semantics, (a) ordinary users of a language have implicit beliefs about the truth-conditions of sentences in that language, and (b) they often agree on those beliefs. For example, it is assumed that if Anna and John are both competent users of English and the former utters `grass is green' in conversation with the latter, they will both believe that that sentence is true if and only if grass is green. These assumptions play an important role in an intuitively compelling picture of communication, according to which successful communication through literal assertoric utterances is normally effected thanks to our shared beliefs about the truth-conditions of the sentences uttered in the course of the conversation. Against these standard assumptions, this paper argues that the participants in a conversation rarely have the same beliefs about the truth-conditions of the sentences involved in a linguistic interaction. More precisely, it argues for Variance, the thesis that, for most linguistic interactions and most sentences used in those interactions, there is no proposition such that all the participants in the interaction believe that the sentence as it was used in the interaction is true if and only if that proposition is true. If Variance is true, we must reject the standard picture of communication. Towards the end of the paper I identify three ways in which ordinary conversations can be communication-like despite the truth of Variance and argue that the most natural amendments of the standard picture fail to explain them. - Weak speech reports. 2018. Philosophical Studies (Abstract, Pre-print)

Indirect speech reports can be true even if they attribute to the speaker the saying of something weaker than what she in fact expressed, yet not all weakenings of what the speaker expressed yield true reports. For example, if Anna utters `Bob and Carla passed the exam', we can accurately report her as having said that Carla passed the exam, but we can not accurately report her as having said that either it rains or it does not, or that either Carla passed the exam or pandas are cute. This paper offers an analysis of speech reports that distinguishes weakenings of what the speaker expressed that yield true reports from weakenings that do not. According to this analysis, speech reports are not only sensitive to the informational content of what the speaker expressed, but also to the possibilities a speaker raises in making an utterance. For example, `Anna said that Carla passed the exam or pandas are cute' is not an accurate report of what Anna said by uttering `Bob and Carla passed the exam' because it characterizes Anna as having raised the possibility that pandas are cute, yet Anna did not raise that possibility through her utterance. As I argue, this analysis has important advantages over its most promising competitors, including views based on work by Barwise and Perry (1983), views appealing to recent work on the notion of content parthood by Fine (2015) and Yablo(2014), and Richard's (1998) proposal appealing to structured propositions. - Semantic Variance. 2018. PhD thesis. New York University (Abstract)

I argue for Semantic Variance, the thesis that for nearly every utterance and any two language users, there is no proposition that those two language users believe to be that utterance's truth-conditional content. I argue that Semantic Variance is problematic for standard theories concerning the nature of communication, the epistemic significance of ordinary disputes, and the semantics of speech reports. In response to the problems arising from the truth of Semantic Variance, I develop new accounts of the transmission of relevant information, ordinary disputes, and the semantics of speech reports using truthmaker semantics. Towards the end of the dissertation I outline a pluralistic account about the nature of communication and linguistic competence.

Under review

- A paper about vagueness

- A paper about the law of non-contradiction

In progress

- Only wholes, but also their parts (Abstract)

We have an apple, an orange and a box. If the apple is in the box, then at least some of the apple's parts are in the box. But the apple's parts are distinct from the apple itself. So if the apple is in the box, then there are at least two things in the box: the apple and at least one of its parts. So it can't be that only the apple is in the box. In this paper, I use a scalar analysis of "only" to explain what goes wrong with this specious reasoning: one can't infer that not only x is F from the fact that at least two things are F. Along the way, I argue that standard diagnoses of the problem using domain restriction are mistaken and that, contrary to most recent literature, "only" doesn't interact with contextually available information in a way that would help with the puzzle. - Graded understanding (Abstract)

I say that I like apples, bananas and strawberries, but it's loud, you can't hear my whole sentence, and you think I only said that I like apples and bananas. An eavesdropper heard even less of my sentence and thinks I only said that I like apples. Neither you nor the eavesdropper understand what I said perfectly, but both understand it at least in part and, moreover, you understand it better than the eavesdropper. This paper builds on earlier work to develop a theory of what it is for someone to understand an utterance better than someone else. I regiment the phenomenon of graded understanding and offer a theory using truthmaker semantics and probability measures. The resulting proposal has important advantages over alternatives which use counting measures, and even over Iacona's sophisticated approach using quantitative supervaluationism.

Talks

Email for handouts

- Operators of structural enrichment (Abstract, Haskell code)

It is customary to think of the semantic values of declarative sentences as unstructured sets of possible worlds. However, for the purposes of the semantics of attitude ascriptions, it is advantageous to think that the semantic values of that-clauses embedding declarative sentences are more fine-grained entities: structured propositions. Prima facie, and given the assumption that ordinary language is compositional, these two approaches seem incompatible: once we compute the semantic value of a sentence embedded in a that-clause, all we have is a set of possible worlds from which no further structure can be recovered. It is thus mysterious how the semantic value of a that-clause could be a structured proposition even though the semantic value of the embedded sentence is just a set of possible worlds. In this talk I argue that we can solve the mystery by introducing a new kind of operator, which I call an operator of structural enrichment, and I offer a recursive semantics for a language containing such an operator. The resulting semantics vindicates Cresswell's (1985) claim that unembedded sentences denote sets of possible worlds and that-clauses denote structured propositions, and the general use of structured propositions in contemporary semantic theory. - A puzzle about mental content (Abstract)

I argue that the kind of reasoning that motivates social externalism about mental content has puzzling consequences for agents who belong to many linguistic communities. I argue that this motivates a radical version of internalism about mental content.

Not currently in progress

- Why quasi-realists are disingenuous (with Harjit Bhogal, Dan Waxman and Mike Zhao)

Teaching

- Central Problems of Philosophy, Summer 2015 (Syllabus, lecture notes)

- 1. Introduction (PDF)

- 2. The human good (PDF)

- 3. Aristotle's account of the good (PDF)

- 4. Virtue (PDF)

- 5. Varieties of consequentialism (PDF)

- 6. Railton: Alienation, consequentialism, and the demands of morality (PDF)

- 7. Wolf and Nagel on the meaning of life (PDF)

- 8. Is death bad? (PDF)

- 9. Williams on the tedium of immortality (PDF)

- 10. Locke on personal identity (PDF)

- 11. More on personal identity (1) (PDF)

- 12. More on personal identity (2) (PDF)

- 13. Frege on sense and reference (1) (PDF)

- 14. Frege on sense and reference (2) (PDF)

- 15. Russell on definite descriptions (PDF)

- 16. Kripke's objections to Russell's theory of names (PDF)

- 17. Perry on De Se belief attributions (PDF)

- 18. Substance Dualism (PDF)

- 19. An argument against dualism; the Turing test (PDF)

- Philosophy of Mind, Summer 2014 (Syllabus, lecture notes)

- 1. What is philosophy of mind? (PDF)

- 2. Substance dualism (1) (PDF)

- 3. Substance dualism (2) (PDF)

- 4. Identity theory (PDF)

- 5. An argument against dualism and the Turing test (PDF)

- 6. Behaviorism (PDF)

- 7. Introducing functionalism (PDF)

- 8. More on machine functionalism (PDF)

- 9. David Lewis: Psychophysical and theoretical identifications (PDF)

- 10. Block's objections to functionalism (PDF)

- 11. Lewis defends commonsense functionalism (PDF)

- 12. Mental causation (PDF)

- 13. Intentionality as the mark of the mental (PDF)

- 14. Dretske: A recipe for thought (PDF)

- 15. Millikan: Biosemantics (PDF)

- 16. Inferentialism (PDF)

- 17. Tying it up: thoughts and intentionality (PDF)

- 18. Propositional attitudes and the language of thought (PDF)

- 19. The intentional strategy (PDF)

- 20. Eliminative materialism (PDF)

- 21. Nagel on conscious experience (PDF)

- 22. The knowledge argument (PDF)

- 23. Loar's response to the knowledge argument (PDF)

- 24. The extended mind (PDF)

Random

BlindIt, an anonymizing script

I used to ask my students to anonymize their papers by naming their file with just their university ID numbers. Unfortunately, at some point I started to accidentally memorize the ID numbers, which defeated the point of anonymizing the papers in the first place. That's when I wrote blindIt.

BlindIt is a bash script. It takes all the files in a given folder and renames them with arbitrary numbers. Once the grading is done, you can run blindIt again to assign each file its original name. You can download blindIt here and consult the instructions for usage and installation here.

For the time being, blindIt runs only on Linux and Mac, but I suspect it can be run on Windows using this. If you're using OS X El Capitan or newer, you may have problems with the installation script. I'll fix those problems if there is interest.

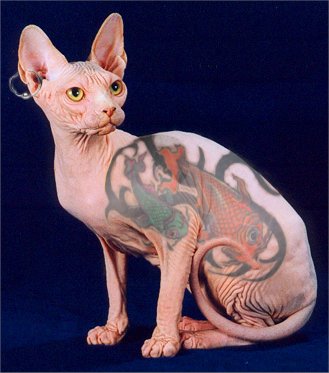

A cat

I don't own the rights for this photo, so let me know if you know whom I should credit.